I recently sat down for a conversation with Emmett Harsin Drager, a PhD candidate in American Studies and Ethnicity at USC Dornsife. Emmett’s research focuses on the period of time in the United States during the 1960’s and 1970’s when research universities began performing gender reassignment surgeries. Thousands of people wrote to universities requesting sex change operations. Some were accepted while others were denied. How did doctors decide who qualified for surgery and who didn’t? The answer is, in part, the subject of Emmett’s dissertation. Specifically, they focus on the history of gender identity disorder and the development of official diagnosis and treatment protocols for transsexual patients.

Emmett Harsin Drager, PhD candidate in American Studies and Ethnicity

Emmett Harsin Drager, PhD candidate in American Studies and Ethnicity

Here are the top 6 things I learned about Emmett’s research and the developing field of transgender studies from our conversation.

1. Transgender and transsexuality are not the same.

The term transgender is used to characterize gender identity or gender expression that

doesn’t conform to social expectations based on assigned sex at birth. Transsexuality

refers to the desire or practice of making physical changes to the body, often through

gender reassignment surgery or hormone therapy. Those who identify as transgender

may not identify as transsexual.

2. Christine Jorgensen may be the biggest celebrity you’ve never heard of.

Christine was one of the first well-documented persons in the United States to undergo a sex change operation. In the early 1950’s, Christine travelled to Europe for the new procedure and returned to an abundance of American media attention. Even though this was during the Korean and Cold War, sensationalized news coverage about Christine dominated the news. Emmett explained that Christine’s story, along with many other sensationalized tabloid stories about transexuals, exposed the possibility of gender reassignment and unleashed a new demand for the procedure in the United States.

3. Doctors used to be the gatekeepers of sex change operations. Today, insurance

companies play a similar role.

Emmett uses archived correspondences from individuals who were denied gender

reassignment surgeries to determine the criteria that doctors used to make their

decisions. Today, doctors generally no longer make that distinction. Rather, insurance

companies require someone who requests a sex change operation to have an official

diagnosis from a psychologist.

4. Assumptions about trans individuals were rooted in perceptions about race.

Emmet explained that the original diagnosis of transsexuality was believed to be the

result of an unhealthy relationship with a parent. At the same time, racial attitudes about

the black family also led to pervasive pathologization. Emmett used the example of Mrs. G, described as a very masculine black woman. Doctors pinpointed Mrs. G’s close

relationship with her single mom as the reason behind her transsexuality, echoing the

conclusions of the infamous Moynihan report that blamed black mothers for social and

economic stagnation.

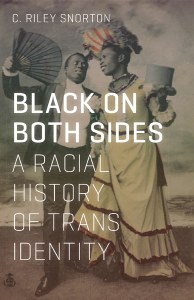

USC Professor C. Riley Snorton, one of Emmett’s mentors and an expert in trans

studies, recently published a book that puts racial formation at the forefront of

transgender studies titled Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans.

University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

5. A lot has changed in the medical community surrounding the diagnosis of transsexuality. But a lot hasn’t.

Transsexuality was originally termed Gender Identity Disorder by the medical

community and classified as a mental illness in the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Although today the term has been changed from

gender identity disorder to gender dysphoria, which serves to destigmatize transsexuality, gender dysphoria is still included in the DSM.

6. There’s more to come at USC!

In the fall of 2018, Emmett will host a plenary on gender and sexuality as part of USC

Annenberg’s Critical Mediations Conference. The conference is scheduled for October

4-5, so be sure to mark your calendars!