When you think of cancer, you hardly think of beauty. You likely think of a destructive disease that wreaks havoc on the body and causes heartache and suffering for millions of people around the world. However, if you look at the process of diagnosing cancer from a purely aesthetic perspective, you could confuse it for art. The colorful tissue biopsies and stains that are used to identify, subtype and select treatments for cancer can look a lot like photographs, water colors or oil paintings intended to hang on a wall.

Rishi Rawat, an MD-PhD student at the University of Southern California, encountered the striking aesthetics during his research to develop digital pathology. Rawat submitted an image taken during his examination of cancer cells to the USC Graduate School’s annual “Deck Our Halls” competition. The competition is designed to showcase student research and creative work in its many different forms. Students submit their projects and those who are selected display their pieces on the walls of the graduate school office for one year. Rawat will exhibit an image of a slide that is part of his cancer research.

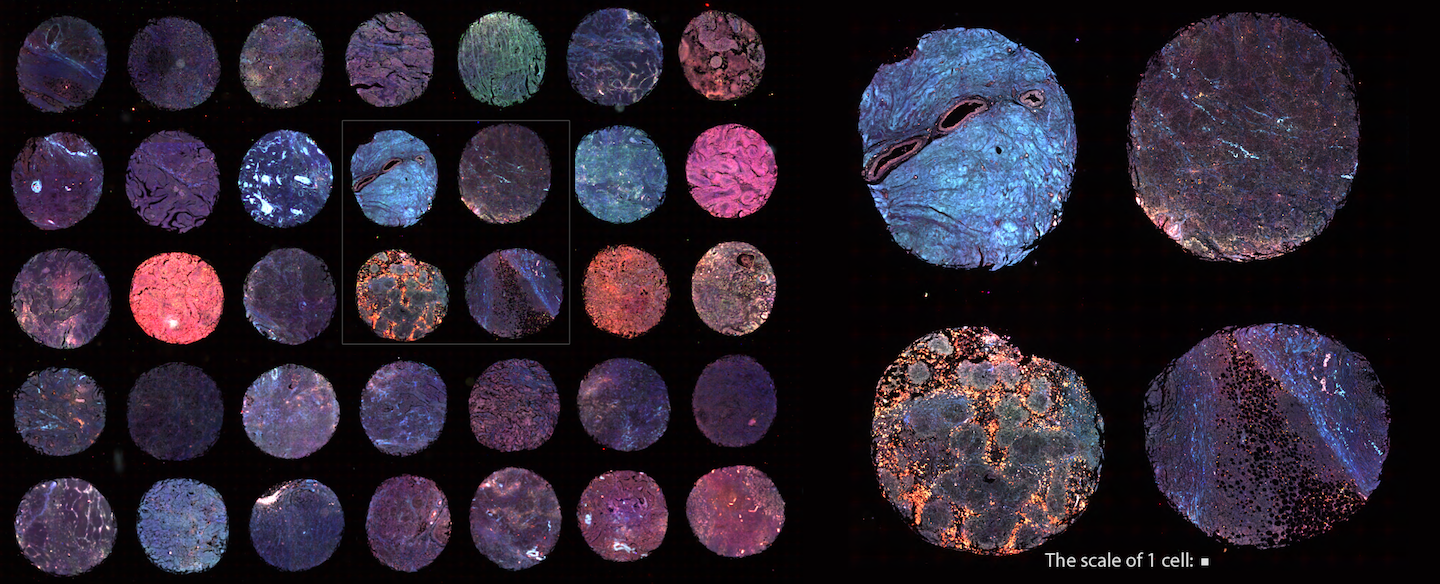

“This is a picture of the natural fluorescence of 35 pieces of cancer tissue without any dyes and stains, just the intrinsic, naked fluorescence of the cells,” said Rawat. “As a person, looking at this image gives me the chills because if I didn’t know it was cancer, I’d think it was beautiful.”

Rawat is working on groundbreaking research that could revolutionize the way cancer is diagnosed and treated. The idea behind digital pathology is to use technology and artificial intelligence to analyze cells and tissue and detect abnormalities. It has major implications in cancer research as a computer is able to recognize cell patterns more quickly than a human. Rawat says digital pathology could reduce the amount of time it takes to diagnose a disease and allow patients to start treatment faster. It can also be used in situations where doctors are not readily available to diagnose cancer.

“If you go to places where they barely have the technologies to take the biopsy and perform the simple stains, they don’t have the expertise to look at that biopsy and give you a deep comprehensive analysis. But, a computer could do that,” said Rawat. “A computer could learn patterns from the tissue, patterns that it learns on its own automatically and patterns that we teach it from the expertise of pathologists, and we could democratize pathology.”

Digital pathology has the potential to improve our understanding of cancer. Rawat says a computer can learn from far more data points than a human, meaning a computer has the potential to learn patterns and discrepancies that go beyond our visual understanding of cancer.

“It could teach us things that we don’t know,” said Rawat. “The more we study cancer, the more we realize it is an extremely complex disease. Computers are going to be able to help us synthesize all of the knowledge that exists into a framework that we can use to think about it more intelligently.”

Interdisciplinary research is central to Rawat’s work. He currently has four mentors at USC’s Keck School of Medicine and USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering who come from a variety of backgrounds: David Augus, a professor in both the medical and engineering schools; Dan Ruderman, a professor at the Keck School of medicine who has a background in physics; Fae Sha, a professor at Viterbi who specializes in artificial intelligence and machine learning; and Michael Press, a professor in the Department of Pathology at Keck and an expert in breast cancer pathology.

Rawat earned his undergraduate degree from the University of California at Berkley and says he decided to continue his education at USC because of unparalleled access to the best professors in each field. “This particular project and this program not only connected me to the best medical people, but to people in other fields who could help me grow in a multidimensional way,” said Rawat.

Rawat’s image of cancer cells will be displayed in the USC Graduate School offices through the year alongside the work of about 30 other USC graduate students. In February, USC Graduate School and the Office of Undergraduate Programs hosted a reception and invited the USC community to see the new creative works decorating the walls.