Mysteries of the heart are explored through literature, poetry, and cinema, requiring us to examine and reexamine great loves and great loves lost. But what about the mysteries of an actual “broken heart” – the medical questions that surround when our hearts do not work the way they are intended to do. Prashan De Zoysa, a Ph.D. candidate and Dr. Ram Kumar Subramanyan at the Keck School of Medicine, spoke with the Graduate School about their research and the question: “Why, despite commitment, does a heart break?”

VR: As someone not in the medical sciences, can you tell me more about what you are researching.

what you are researching.

Subramanyan: Early in development, progenitor cells in specific regions of the embryo commit themselves to becoming a heart, well before they start to form. We study the mechanisms that control the integration of these committed progenitor cells to develop into a normal heart.

VR: Essentially, certain cells, progenitor cells, are destined to develop into heart cells. Your research focuses on the mechanisms that decide and control the committed cells and your most curious about when those committed cells fail to form a healthy heart.

VR: What is the potential impact your work has to change the medical profession/health of individuals and communities?

De Zoysa: Congenital Heart Defects (CHDs) are the most common types of birth defects affecting nearly 1% (about 40,000) births per year. Outflow Tract defects are the majority of these CHDs. My graduate research work is involved in studying the role of a certain molecule’s signaling (Delta Like Ligand 4/DLL-4) in cells that are committed to become the OutFlow Tract. Interestingly, the principles that govern heart development also play a role in heart regeneration following injury, for example recovering from a heart attack. If we understand how molecular interactions help early progenitor cells commit to the developing heart during the early stages of development, we may also learn more about the heart’s ability to regenerate.

Subramanyan: Understanding heart development is a worthwhile exercise in many ways. First, it unravels the unique mysteries associated with the development of one of the most special organs in the human body. The heart begins to beat at about 2 to 3 weeks after conception, at a time when the mother is not even aware that she is pregnant. And life stops when the heart stops beating. After all, there has to be a reason why Valentine’s day is celebrated to honor “sweethearts” and not, say, sweet kidneys! Second, understanding the processes that go awry during development, provides a molecular perspective on the clinical heart diseases that children may be born with. This offers unique insights into potentially novel therapeutic approaches that may not be apparent to the clinician. Lastly, as Prashan stated, developmental principles are called back into action when the adult heart recovers from injury. Therefore, being able to recapitulate the accurate developmental events is key to the regeneration and repair of the damaged heart.

VR: Prashan, why did you decide to work/pursue your PhD at USC?

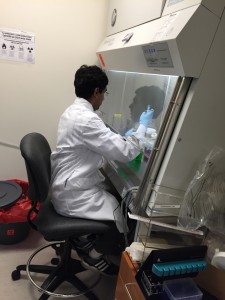

De Zoysa: I decided to attend USC due to its reputation as an institution that fosters scientific collaboration among its researchers. This was readily evident in the visits to different labs during the interview process. Upon entering the university as a Ph.D. candidate, I could see these collaborations first-hand in the numerous labs I rotated through during my first year. Also, the scientific environment at USC genuinely fosters the growth of developing scientists and is an ideal setting for the heart development project that I’m involved with. There is a robust Development and Stem Cell Biology group at the Broad CIRM Center of USC at the Health Sciences Campus which hosts a weekly research seminar series in Stem Cell and Developmental Biology, where graduate students and postdoctoral fellows present their research work to their peers. Attending these seminars has enlightened me about the research work that is carried out by the various faculty at USC and has sometimes given me ideas about experimental approaches that can be utilized in my own research.

For similar reasons I decided to join Dr Ram Kumar Subramanyan’s lab. Dr. Subramanyan is a cardiac surgeon-scientist who not only understands heart development but is also involved in clinical care of children with CHDs. I believed he will be in a better position to relate the findings of my research work to a real life clinical setting that will potentially be applied to not only heart development but also heart regeneration.

Considering all this, I believe that the doctoral training I am currently involved with in the Development Stem Cell and Regenerative (DSR) program at USC is ideally suited for me to pursue my current research and will pave the way to my long term goal of becoming an academic researcher.

We at the graduate school are thankful for such great Ph.D. candidates and world-class faculty to guide our researchers. Happy Valentine’s Day to all!

Prashan graduated summa cum laude from California State Polytechnic University Pomona in 2011 with a bachelor degree in microbiology with a minor in chemistry. During his undergraduate studies and post baccalaureate work at Cal Poly Pomona, he worked in the laboratories of Dr. Wei-Jen Lin and Dr. Bijay Pal focusing on bacterial and malaria research.

About Ram Kumar Subramanyan, MD, Ph.D.

Ram Kumar Subramanyan, MD, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of Surgery and Pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. After completing his medical education at Madras Medical College, India, Dr. Subramanyan moved to the United States and completed his general surgery residency in 2008 under the chairmanship of Tom R. DeMeester, MD. He then continued his cardiothoracic surgery training and Congenital Cardiac Surgery Fellowship under Vaughn A. Starnes, MD.